Holden Caulfield wasn’t just asking about ducks. He was asking if anyone still cares about fragile things, a question our kids are still asking today.

Author’s note: This is the first in a new series roughly called A Curriculum of Dissent. Talking with my kids about books that will help them thrive and survive in a divided algorithm age.

#

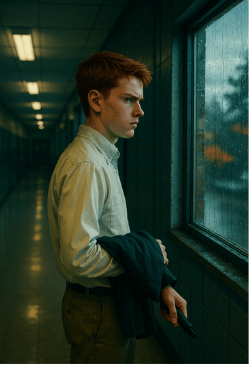

My son came into my home office asking if I will help him understand something he was reading for homework. Luckily he was reading The Catcher in the Rye. I was very happy to see that schools still have this book on their required reding list. I love this book so much that my son’s middle name is Holden.

He was struggling to understand why a story about a well to do kid from Manhattan in the 1950’s was so important to him, a middle class suburban kid in 2025? Fair question.

Specifically he complained to me,

“I don’t get why he keeps asking about the ducks in Central Park.”

That comment cut me to my very core. To me, Holden’s questions about the ducks are the most important theme of the book. (Yes, there are many others. But to me, the ducks are the most important.)

“Easy,” I replied. “Empathy.”

“Empathy for ducks?” He looked at me more puzzled than when he came in.

“Empathy for all,” I replied. “In The Catcher in the Rye, Holden asks about the ducks four separate times in four separate chapters,” I explained.

“In Chapter 2 Holden says;

‘I live in New York, and I was thinking about the lagoon in Central Park, down near Central Park South. I was wondering where the ducks went when the lagoon got all icy and frozen over.’

In Chapter 9 he says again

‘You know those ducks in that lagoon right near Central Park South? That little lake? By any chance, do you happen to know where they go, the ducks, when it gets all frozen over?’

In Chapter 12 he keeps looking for an answer;

‘Hey, listen,’ I said. ‘You know those ducks in that lagoon right near Central Park South? That little lake? By any chance, do you happen to know where they go, the ducks, when it gets all frozen over? Do you happen to know, by any chance?’

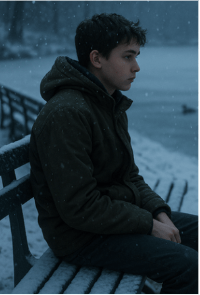

In Chapter 20, toward the end, Holden actually goes to Central Park to look for the ducks himself. It’s freezing, he’s half delirious, and he can’t find them.

He ends up sitting alone on a bench, feeling sick and scared. “

He doesn’t find the ducks.

They symbolize what he’s searching for, something fragile that survives as their world turns cold. He’s trying to practice empathy. And he’s looking for someone who feels the same. And he’s struggling to find it.

Holden asks himself. But Salinger is really asking us:

“When things get cold and dark, where do the good things go? And do they ever come back?”

Even though this book is 74 years old, our kids also feel the same anxiety, fear of change and lack of empathy as Holden does. Our world is getting colder. Our world is getting more harsh. And as our kids build up their defenses against it, their sense of empathy is slowly crushed. Every adult in the book answers Holden’s question in a similar tone:

“How the hell should I know?” he said. “How the hell should I know a stupid thing like that?”

That’s a metaphor for us, the parents, adults, or role models in a young person’s life. If we can’t show empathy, they can’t model it.

When Holden asks about the ducks, he’s asking, “Does anyone care about small, fragile things?”

Why does he ask this? Two reasons: first Holden sees himself as one of the small fragile things. His world is falling apart and it’s overwhelming him. That’s a feeling our kids today still feel except multiplied by ten with the addition of Social Media, the rise in fascism and the overwhelming tidal wave of deep fakes and online bullying. Case in point, people cheered when DOGE shut down USAID. As a result 5 million kids under the gage of 5 will die from starvation and disease by they year 2030. “Does anyone care about small, fragile things?”

Holden’s simple question, “Where do they go?”, is an exposure of his innocence, vulnerability and uncertainty in this time of change. Holden is saying, “Someone should look out for them.” But he’s really asking “Will someone should look out for me?”

When Holden asks about the ducks, he’s testing whether the adults in his world are still capable of caring about something small and helpless. Their blank or irritated responses prove they’re not. He’s irritated and his anxiety increases not because of how the adults are. He’s irritated because he sees his future. He fears that’s how he, and all members of his generation, will grow to be.

Every time he asks that question, he’s really saying, “Is anyone out there still capable of caring about something small?” and every adult answers with “How the hell should I know?”

“Why is this important to read?” I ask my son. I don’t wait for an answer. “Holden’s question is really a lesson in empathy as survival.”

“Survival?” my son counters. “Isn’t that a bit dramatic dad?”

“Not physical survival,” I push pack. “Caring about something other than yourself, even something as simple as a duck, is how we stay human in a cold world.”

It’s the same energy that makes Holden adore his younger sister Phoebe, defend innocence, and want to be “the catcher in the rye”, the one who saves kids before they fall. His empathy is refusal to let the world harden him.

So when my son’s teacher is asking questions about ducks, he’s not looking for an answer. He’s looking for a dialog. And I think the dialog needs to be:

Can’t we all use a few more Holden Caulfields in our world these days?